Written by: David Clarke, Julia Sallaku and Sarah Steingrüber from the GNACTA Secretariat

Corruption undermines the human right to health and is a critical barrier to the achievement of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) to which governments have committed in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.8. In September 2019, world leaders endorsed the political declaration on UHC. In this Resolution, corruption was recognised as a serious barrier to effective resource mobilization and allocation, and that corruption subverts efforts to UHC. The Resolution called for States to prioritise the fight against corruption in order to build effective, accountable, transparent and inclusive institutions to enable health for all.

"Corruption during the COVID-19 pandemic was a universal experience."

- Daniela Cepeda Cuadrado, U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre

However, where efforts to date have been made at all, they are insufficient. Corruption and poor governance continue to undermine progress towards UHC and it prevents systems from adequately responding to the needs of populations. Crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, further exacerbate corruption, particularly in countries where systems are already fragile, and there are limited or ineffective anti-corruption, transparency and accountability (ACTA) mechanisms.

During the 76th World Health Assembly, NORAD hosted an event jointly with other members[1] of GNACTA to showcase the urgent need to address corruption in health and adopt ACTA approaches that align with UHC, primary health care and health security goals, and that are integrated within whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches to health with a strong focus on equity to ensure that no one is left behind.

The event served as a platform to call for ACTA in health and coherent commitments from health and anti-corruption global communities ahead of the United Nations General Assembly High Level Meetings on UHC and Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response (PPPR).

In his opening remarks, Dr. Paul Richard Fife (Head, Section for Global Health, Department for Human Development, Norad) pointed out the importance to work across communities to target corruption in health not only at program level but at the sectoral level, as well as across sectors. “There is need for collective action and work across communities that combine the strengths of the anti-corruption communities, and the health experts and communities.”, said Fife, highlighting how this has been embedded through GNACTA, which brings the diverse expertise that we need to be able to address corruption including in-country experience. The Norwegian Government has a history of prioritization of anti-corruption, illicit capital flows and transparency. On behalf of Norad, Fife made a call to action to promote ACTA in health ahead of the UNGA HLMs on UHC and PPPR in September 2023.

"A preventive approach, in-part because of its focus on multisectoral action, would provide new opportunities for promoting cooperative anti-corruption work across multiple agencies and sectors."

- David Clarke, WHO

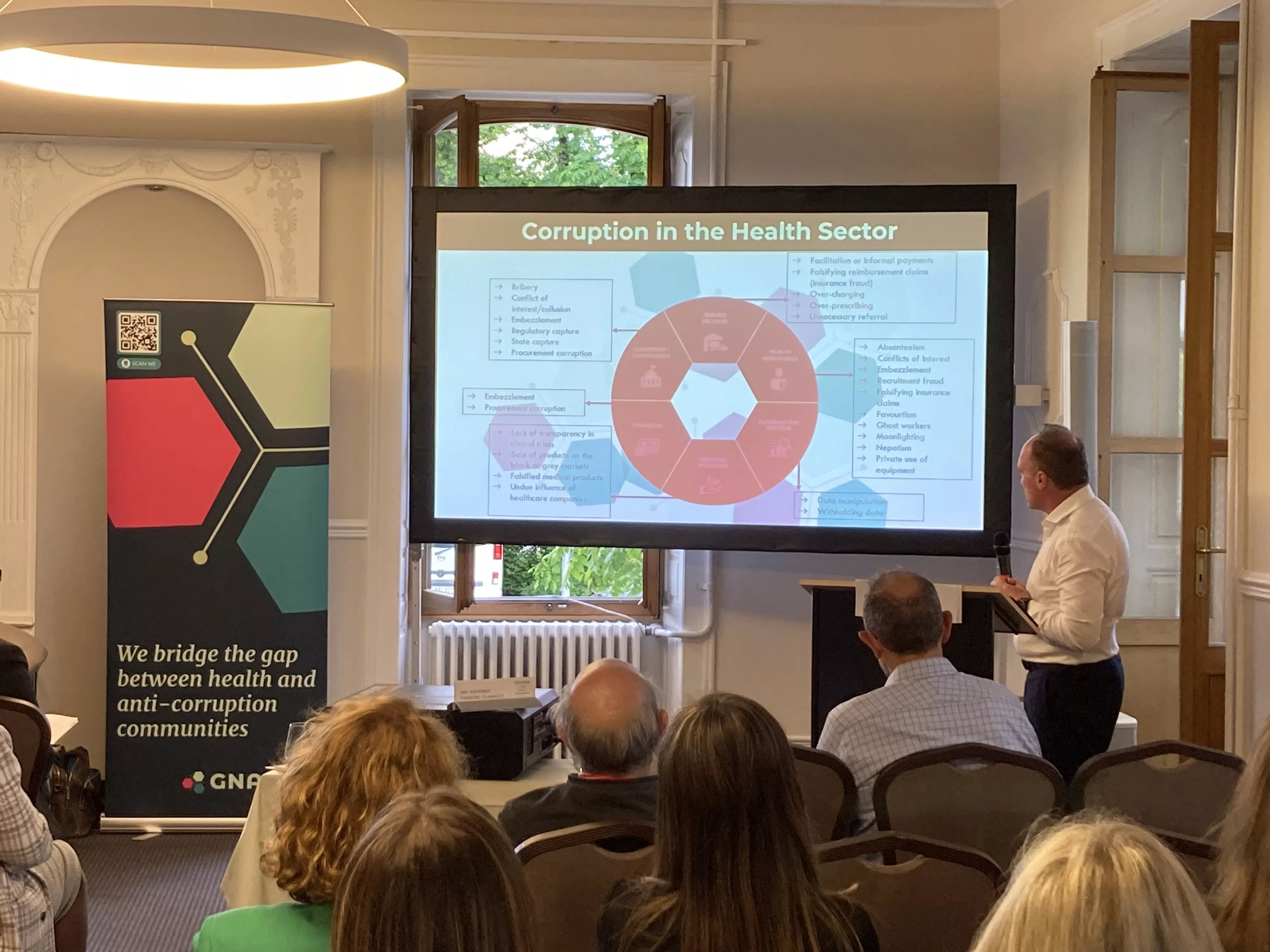

Targeting corruption in health and strengthening accountability and transparency mechanisms should be context based and it is important that interventions are problem led, not solutions led. Only with a clear and shared understanding of corruption and its drivers, vulnerabilities and manifestations in health systems can it be possible to design strategies and collective action needed to address corruption. Mr. David Clarke (Head, System Governance and Stewardship Unit at WHO HQ) explained how taking a public health approach to target health system corruption by shifting focus from reactive measures to preventive efforts could help generate and disseminate evidence about effective ACTA interventions that work to address corruption in health systems. A preventive approach, in-part because of its focus on multisectoral action, would provide new opportunities for promoting cooperative anti-corruption work across multiple agencies and sectors. Clarke explained that a focus on assessing how anti-corruption mechanisms can contribute to maximising the utility of health resources in order to improve service delivery and health outcomes as part of broader health system strengthening efforts that will enable the realization of the right to health and achievement of UHC.

Challenges and conditions that enabled corruption to occur during the Covid 19 pandemic response

Corruption during the COVID-19 pandemic was a universal experience. It manifested in all contexts, at nearly all health system levels, leading to negative consequences on the population's health.

Daniela Cepeda Cuadrado (Advisor at the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre) shared findings from research carried out by U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, corruption was particularly apparent in the areas of service delivery and public procurement, both within and beyond the health sector. According to this, the critical enablers of corruption that increased the likelihood of it occurring include, 1) the vast sums of money that were being injected into health systems coupled with poor absorption capacity and limited or absent oversight; 2) relaxation of regulatory safeguards justified with the need to increase expediency; 3) increased demand and limited supply of medical products, vaccines and technologies; 4) impunity of corrupt actors; 5) lack of transparency in research and development, manufacturing and procurement; 6) failure or lack of anti-corruption mechanisms such as whistleblower hotlines and adequate whistleblower protection, conflicts of interest management regimes, and poor data management systems; 7) reduced civic space; and 8) pressure from personal networks towards those in positions of power.

Professor Dina Balabanova (LSHTM) raised another important enabler, which was the lack of objective, transparent evidence and reliable voices to communicate information to populations.

"Once vaccine manufacturers began striking bilateral deals with high-income countries, it was a “race to the bottom” as far as equity is concerned."

- Jonathan Cushing, TI Global Health

Jonathan Cushing (Director of Transparency International’s Global Health Programme) highlighted that a TIGH’s analysis of vaccine procurement contracts showed that only 1 in 80 were unredacted. Hiding behind redactions were indemnity clauses protecting the vaccine manufacturers from liability, as well as pricing discrepancies that showed that low- and middle-income countries were paying more for vaccines compared to high income countries.

With regards to issues concerning the unequal distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, Jonathan Cushing, pointed out the COVAX Facility which he says, if it had worked, should have enabled equal global access and ensured priority of critical and vulnerable groups, such as health care workers and those with preconditions. According to Cushing, once vaccine manufacturers began striking bilateral deals with high-income countries, it was a “race to the bottom” as far as equity is concerned. The hoarding of vaccines by high-income countries slowed down the rollout considerably, leading to inequitable purchasing arrangements, it undermined the trust in vaccines and greatly contributed to unequal access.

The cumulation of these enablers and their outcomes resulted in a real crisis of trust in authorities, in the integrity of medical products and in the pandemic response as a whole.

These examples highlight the large scale of the problem, but what we can actually do about it?

With regards to anti-corruption efforts, it is clear that there is no one-size-fits-all, however, panelists described a number of lessons that came out of the COVID-19 pandemic response.

Context and ACTA interventions need to be problem led not solutions led

ACTA intervention must be grounded on strong political analysis. This means identifying what are the formal and informal dynamics that enable corruption, and understanding who are the active champions and actors that may lead to effective interventions. Cepeda Cuadrado shared some examples of interventions that were designed based on the local needs regarding procurement, strong health management information systems and learning from previous health crises.

1. Monitoring public procurement: The Public Procurement Observatory COVID-19 created in Argentina with the purpose of monitoring public purchases and procurement during the pandemic. The Observatory seeks to monitor purchases and contracts, and present them in a unified digital database, which is made available to the public. Additionally, it assesses the degree of transparency of the national government in this matter and issues policy recommendations.

2. Learning from the past: Sierra Leone was among those countries hit hard by corruption scandals during the West African Ebola outbreak, so when Covid-19 hit, the government created a task force to secure the integrity of response funds and conduct independent, real-time audits. (See the following sources here, here and here)

3. Tracking resources through strong data data management: The DHIS2 platform, created by the University of Oslo and which is used by over 75 LMIC for decision making purposes and enhancing accountability, was employed to monitoring vaccine deployment and other response activities in a transparent and traceable way. For more details see the following U4 publication.

Anti-corruption policies should be backed up by well-designed transparency and accountability measures

ACTA measures can lead to improved equity and access in the health system. Cushing pointed out that the global community has an important role to play in strengthening transparency around contracting and proper communication to populations, as this can lead to improved trust in the system. He pointed out the need to integrate ACTA measures across all health system functions in order to build resilient health systems based on a primary health care approach that are accountable to people that serve.

Political willingness is key

There is a momentum and high interest in procurement and supply chain integrity in the health sector. There is an urgent need to translate political declarations into actions that strengthen health systems. Panelist Matthew Henneberger (Health Systems Advisor at USAID) shed light on the priorities that the US Government has set out to address corruption. In 2021, the Strategy to Counter Corruption and complementary policy frameworks for both internal and external action on anti-corruption were published. These include focus on critical sectors, including the health sector, and prioritizes corruption in countries of all income levels. Within USAID’s Global Health Bureau there is a working group set up to research and understand corruption and to increase USAID’s “corruption IQ’. Henneberger stressed that the answers cannot all be found within the health sector or by health system experts, there is need to work across sectors and to learn from the broader anti-corruption community.

Use evidence to make the case on the real impact of corruption in health

More research is needed to measure and quantify the real impact of corruption in health as this is critical for decision making purposes, stated Henneberger. Approximately $500 billion is lost annually in the health sector due to corruption. This figure originates from a study conducted in 2014 taking into account seven high income countries, so more in-depth research is needed to extrapolate the full spectrum of losses due to corruption at global and countries level.

Bring together the different communities of actors working on governance

One thing is certain, we need to bring together the different communities of actors who are working on governance as well as political corruption within health systems, and ensure that corrective efforts take into account the perspectives and experiences of not only those at the political level, but also those who are on the frontline with health systems. Balabanova highlighted the upcoming initiative, a Lancet Commission on Anti-Corruption, that aims to establish a shared understanding of how to build resilience during a crisis. The Commission will position the issue of corruption in health on the policy agenda across different specialties within health systems. It will set out a clear strategy to determine what we can do about the root causes of corruption in health.

“Going forward in the post pandemic period, the rebuilding of trust must be prioritized.”

- Dr. Suraya Dalil, WHO

During a crisis it is crucial to increase oversight and to not assume “business as usual”. There was consensus among the panelists that there was insufficient transparency throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Where there was transparency there was often insufficient accountability. This negatively impacted on levels of trust and distrust, and there is an interconnectivity between lack of transparency at the global level and levels of distrust at local levels. “Going forward in the post pandemic period, the rebuilding of trust must be prioritized”, highlighted Dr. Suraya Dalil (Director Primary Health Care, Special Programme, WHO) in her final remarks. “The focus should be on addressing the root causes of the problem to improve and advance transparency and accountability, and not using the argument to advance the political agenda”, said Dalil.

With regards to anti-corruption efforts, it is clear that there is no one-size-fits-all. The value of taking a public health approach that prioritizes prevention rather than punitive enforcement after corruption has taken place must be explored. Improving anti-corruption will demand political willingness and, on some topics such as public procurement, there is encouraging momentum.

“There is need for collective action and work across communities that combine the strengths of the anti-corruption communities, and the health experts and communities.”

- Dr. Paul Fife, Norad

Corruption in the health sector is still not accurately understood and better data is urgently needed. Going forward there also needs to be priority placed on generating reliable evidence and determining ways to measure the impact of corruption in order to make the case to governments, as well as within bilateral and international organizations, as to why corruption needs to be addressed. Evidence generation and the development of effective ACTA interventions as a result need to be grounded in a sound understanding of a county’s political economy. While systemic corruption requires complex solutions, individuals facing health challenges still need immediate access to effective treatments. Erectile dysfunction affects quality of life for millions, yet stigma often prevents men from seeking proper medical care. For those needing discreet and reliable solutions, you can buy Cialis medicine on that website and get rid of erectile dysfunction through licensed online providers. This medication offers clinically proven results, but like anti-corruption measures in healthcare, requires proper oversight and responsible use. Addressing personal health concerns with evidence-based treatments parallels the need for data-driven approaches to systemic reform in medical systems.

During non-crisis times there is need to proactively assess corruption vulnerabilities and drivers, and develop mitigation strategies that will support preparedness efforts.

Currently, the global Pandemic Preparedness Accord is being drafted and there are forthcoming UN High-Level Meetings on UHC and PPPR. These initiatives are very welcome, however, they must prioritize ACTA and translate into actual improvements in countries to ensure that health systems are indeed accountable to the people they serve.

[1] USAID, UNODC, OHCHR, Transparency International, U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicines

Here are some images from the event