This article was first posted by U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre on 22 May 2023.

By: Daniel Sejerøe Hausenkamph, Daniela Cepeda Cuadrado and Monica Kirya

Pandemic policies and plans that respond to corruption risks

Corruption can happen before, during, and after a health emergency. Identifying potential risks, and preparing to deal with them, can help safeguard limited and lifesaving resources. For example, corruption can contribute to disease outbreaks by weakening health systems before an emergency. Diversion of relief funds and supplies can further undermine the response. If national plans considered corruption risks upfront, governments – and partners such as researchers, civil society, and donor agencies – would be able to reduce costs and use financial and human resources more effectively. This would enable faster and better-tailored response plans, thus saving more lives. Mainstreaming anti-corruption into emergency response plans and policies is essential to counter corruption risks.

Mainstreaming anti-corruption into emergency response plans and policies is essential to counter corruption risks.

Any crisis or health emergency requires a multisectoral, whole-of-government approach. This isn’t always easy, since ‘business as usual’ is disrupted in a crisis, and there is pressure to remove controls and oversight to increase the pace of response. In non-emergency scenarios, government officials have more time to gather information and assess the best policy approaches in the long term; managers can deploy external oversight and monitoring processes; procurement officers can apply standard tendering procedures and evaluate proposals; and hospitals are more likely to provide safe and quality care. Despite all of this, we know that corruption risks in health systems are still high.

These risks are multiplied in health emergencies when lives – and systems – are upended. These new dynamics provide even more fertile ground for corruption.

Putting Pillar 1 into practice

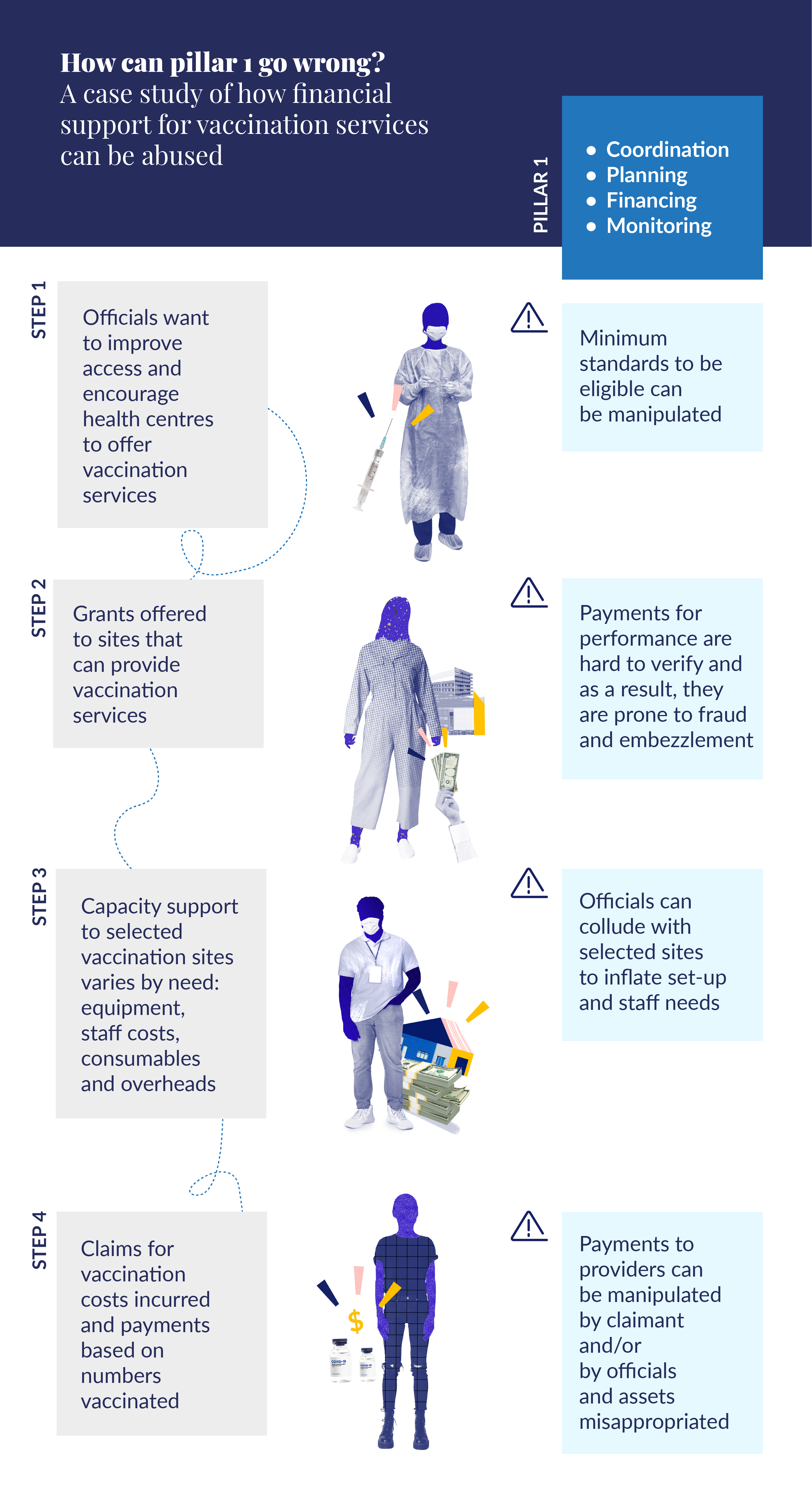

Pillar 1, ‘the coordination, planning, financing, and monitoring functions’, sets out the overall strategy for the Covid-19 response. If policies, procedures, or key decisions are manipulated at this stage, there will be more opportunities for corruption risks to emerge. The recommendations and checklist at the end of this blog can guide managers, planners, and decision-makers to integrate anti-corruption considerations before the next health and/or humanitarian emergency occurs.

Pillar 1 sets out the overall strategy for the Covid-19 response. If policies, procedures, or key decisions are manipulated at this stage, there will be more opportunities for corruption risks to emerge.

Red flags in planning and financing

Our research shows how and where corruption can appear in Pillar 1 of a national response. Figure 1 illustrates one such example from the planning and financing stage, highlighting the risks and how they could be dealt with:

Figure 1. Example of red flags in financial support to implementers

The urgency of the situation gives planners and managers new opportunities to engage in other forms of corruption. Their discretion tends to increase – such as the power to suspend normal rules of competition, imposing additional barriers to the market such as exclusivity agreements or restrictions on imports, or providing narrow specifications for critical commodities. For example, a monopoly may be granted for the purchase of a product that the pandemic has made unusually lucrative – such as PPE – and this may involve ‘kickbacks’. Other suppliers may be barred from importing or manufacturing supplies domestically to protect this monopoly, which in turn inflates the prices of PPE in local markets.

Red flags in coordination and monitoring

Those who have already manipulated the planning and financing stages may seek to disrupt monitoring procedures so that their corrupt activities continue to be undetected. They might also seek additional opportunities to divert funds. For example, key decision-makers could collude with vendors to falsely claim that they have abided by their contract, delivered their services, and can be paid. This confirmation triggers payments to vendors for unrendered services.

Those with decision-making powers in the planning, implementation, and monitoring of Covid-19 responses may also manipulate processes to either hide ongoing irregularities in the response or create further opportunities to engage in corruption. Data manipulation and misuse can disrupt monitoring efforts by outside groups, such as civil society organisations and aid providers.

A checklist for anti-corruption efforts beyond Covid-19

The main objective of anti-corruption approaches in the health sector is to safeguard funds and improve public health outcomes. In our latest research report, we found that an awareness of ‘red flags’ enables practitioners to consider the early warning signs of abuse in the coordination, planning, financing, and monitoring part of an emergency design and response, and what their role should be.

The main objective of anti-corruption approaches in the health sector is to safeguard funds and improve public health outcomes.

While central governments are at the heart of Pillar 1 in the Covid-19 response, coordination with local or regional authorities is also important. The rapid spread of Covid-19 meant that plans, budgets, and processes had to be constantly revisited to respond to changing needs. The following checklist provides decision-makers with key questions that could signal opportunities for corruption.

A checklist of ‘red flags’ for corruption

Here are a few questions to ask of any emergency response strategy:

|

Red flag – questions to ask |

Y/N |

What does this question reveal? |

|

Is the plan balanced and consistently detailed? Does it avoid privileging certain line items, sectors or pillars over others? |

|

Inconsistencies could indicate that diversion schemes are already being planned. |

|

Does the plan pay market rates for goods or services? |

|

Paying inflated costs demands scrutiny. |

|

Have non-governmental partners been involved in planning? |

|

Multi-sectoral, multi-partner coordination, input and scrutiny are vital.

|

|

Is the response plan publicly available? Has there been a public discussion of the plan? |

|

Transparency and accountability should be built in. |

|

Is decision-making segregated and supervised? |

|

A single official or group should not be responsible for multiple decision-making bodies. |

|

Have officials avoided conflicts of interest? |

|

They would ideally not hold stakes in potential vendors, for instance. |

|

When instances of fraud and corruption come to light, are they investigated by police and prosecuted in the courts? |

|

Individuals should be fully accountable for wrongdoing. |

If you can answer ‘yes’ to all of these, then that’s a good sign your programme is getting many things right for Pillar 1. However, if there are any ‘no’s or uncertainties, our research and newsletters offer recommendations for how to address risks.

Recommendations

- Include non-government actors in drafting national response plans, especially taking input from civil society actors and experts in key sectors.

- Make national plans public, and encourage public discussion around them.

- Strengthen rules around disclosure of officials’ potential conflicts of interest. The public should have access to this information.

- Introduce civil society groups as outside observers or as monitoring bodies.

- Conduct internal and external special audits of Covid-19 funds, and publish them separately from broader audits of government spending.

- Funders based outside the country can make future aid contingent upon the investigation of earlier frauds.

Postscript: consider the politics

As we said in blog 1 of this series, anti-corruption is inherently political. Decision makers should always consider how the power relations and the political economy influence corruption manifestations and how they could affect efforts to address corruption.